Minority Report

Grade: A

In the early 2000s, Steven Spielberg went through a cynical sci-fi phase that resulted in two of his most underrated and prophetic films: A.I. and Minority Report. Starring Tom Cruise, the latter is a thought-provoking blend of mystery, action and compelling moral drama that ranks as one of the most entertaining films of Spielberg’s career. In terms of action, Minority Report is right up there with Jaws, Indiana Jones and Jurassic Park.

Directing:

Spielberg trades his signature sense of classical wonder for a timely sense of postmodern pessimism. His Minority Report is awash in over-lit desaturated colors, providing a bleak, corporate visualization of a near-future dystopia (similar to A.I.). The blinding, bleached mise en scène works incredibly well: Washington, D.C. in 2054 is an artificial land where crimes can be predicted before they happen, where the grey areas of human nature are, for better or worse, being eliminated. The sickly white sheen overpowers any sense of sci-fi astonishment.

Even though Spielberg’s visuals bear a few passing similarities to George Lucas’ Star Wars prequels (Attack of the Clones was also released in 2002, and Obi-Wan Kenobi’s trip to Kamino uses a similar color palette), Minority Report bears more similarities to black-and-white noir films like John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon and The Asphalt Jungle, while also being a spiritual successor of sorts to Ridley Scott’s neo-noir Blade Runner. Still, Minority Report is unmistakably Spielberg. Only a filmmaker of his caliber could add a family-friendly sense of humor (mainly as sight gags during the chase sequences) to such a serious thriller.

Acting:

Beginning in 1999, Tom Cruise went on an incredible prestige run in which he starred in films directed by Spielberg, Stanley Kubrick and Paul Thomas Anderson. Of the three, Minority Report features Cruise’s most traditional character: a bulked-up, constantly running chief of police named John Anderton, who is framed for a murder he’ll never commit. It’s a role in which his masculinity is constantly and compellingly humiliated (which was also a subtle hallmark of Eyes Wide Shut and Magnolia). Anderton’s physical vulnerability makes us invested in his investigation and sympathetic to his plight.

But he’s not the only actor with charisma: a young Colin Farrell and an elderly Max Von Sydow both add essential points of view to this multifaceted morality play. And, of course, Samantha Morton’s performance as an almost-inhuman “precog” imbues Minority Report with a necessary creepiness. The colorful performances overcome any perceived clichés or shallow characterizations.

Writing:

There is plenty of exposition throughout the film, but that’s to be expected in a high-concept sci-fi such as this. The lack of subtlety occasionally sticks out, but it renders the complex premise easy to understand. Once the story starts moving, however, the plot is so compelling that we hardly notice that a good portion of the dialogue is merely exposition. Either way, the set-up is well worth it in the end, with several fantastic twists and turns that deliver memorable pay-offs.

Music:

Circa 2002, legendary composer John Williams was busy working on the orchestral scores for Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets and the aforementioned Star Wars: Attack of the Clones. Musical motifs from both movies seem to bleed over to Minority Report, but that ultimately works in its favor by lending a welcoming familiarity to the film’s intricate ideas. It’s a classic Williams soundtrack; one that perfectly colors the storyline with old-school Hollywood grandeur and recognizable motifs.

Ending (SPOILERS):

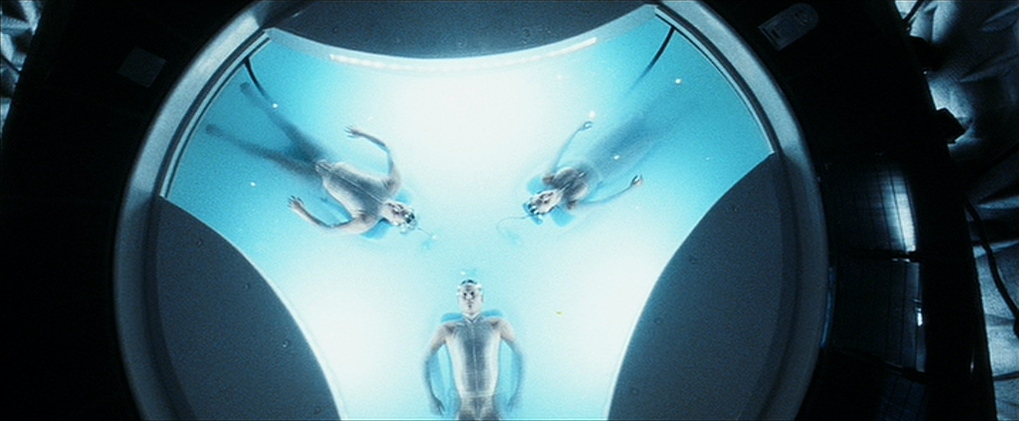

Spielberg can’t help being schmaltzy, right? Up until its final act, Minority Report is a pessimistic, dystopian, true-to-life drama that highlights the follies of man and the dangers of technology. Then, the tidy and contrived ending arrives, which — although crowd-pleasing — is perhaps Spielberg’s most cloyingly sentimental conclusion yet. The final shot and accompanying voiceover are a happily-ever-after that tosses most of the film’s thought-provoking themes out the window: pre-crime is shut down after John Anderton exposes the government’s corruption, and the precogs live the rest of their days in a picturesque secluded mansion.

But what if that was all just a ruse? Perhaps we should pay more attention to when John Anderton is arrested and put into a cryogenic panopticon prison, in which the eccentric jailer tells him: “They say you have visions. That your life flashes before your eyes. That all your dreams come true.” Does this imply that the final 20-or-so minutes of the film are all in John’s head? That would explain why everything works out so conveniently. If so, Minority Report would parallel the ending of A.I. (and Terry Gilliam’s Brazil): the main character is given a manufactured vision of inner peace, and the heartwarming finish is merely a distraction from the harsh dystopia. Although the finale is open to interpretation, I subscribe to the cynical theory. It’s the only time Spielberg uses ambiguity in his entire filmography.

“The fact that you prevented it from happening doesn’t change the fact that it was going to happen.” — John Anderton

Why Minority Report gets an A:

An entertaining, action-packed and mind-bending morality play about freewill, Minority Report is one of Steven Spielberg’s most thought-provoking thrillers.

Accolades:

Colin’s Review Best Films of the 2000s

Discover more from Colin's Review

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.